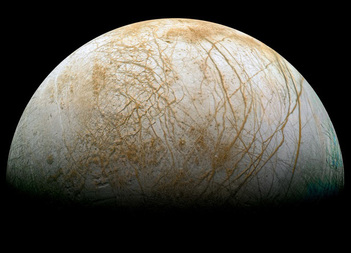

The crazed icy surface of Jupiter's moon Europa.

The crazed icy surface of Jupiter's moon Europa. Europa is one of the four largest moons of Jupiter, called the ‘Galilean moons’ as they were discovered by Galileo when he turned the first telescope on to the giant planet in 1610. Observations by various telescopes and passing spacecraft show Europa as an ‘ice planet’, having the appearance of a white snooker cue ball. However closer examination principally by the spacecraft Galileo, which orbited the planet from 1995 until its suicidal dive into the planets atmosphere in 2003, shows the surface to be crazed with cracks and streaks. It also apparent that surface craters are rare, suggesting a geologically young

surface.

The Hubble Space Telescope.

The Hubble Space Telescope. outer ice crust. Some background to this discovery is discussed briefly on pages 231-232 of the book How Spacecraft Fly. The reason why scientists got so excited about this was the unlikely prospect that Europa may be the only place in the Solar System (other than the Earth) to host life. The logic of the argument is something along the lines of the following. Firstly, the existence of a sub-ice ocean suggests there must be some source of heat energy coming from below the surface to produce and maintain water in a liquid state. The mechanism for this, it was realised, comes from consideration of Europa’s orbit around Jupiter which is elliptical. Consequently, the distance varies by about 13,500 km every orbit period

of 3.55 days. Because Jupiter is so massive, it causes significant tides in the solid structure of the moon. So as Europa orbits, and its distance from Jupiter varies, it is squashed and stretched by Jupiter’s tidal forces. This in turn produces an internal heat source capable of causing volcanic activity in the moon’s core.

The Galileo spacecraft orbited Jupiter 1995-2003.

The Galileo spacecraft orbited Jupiter 1995-2003. These vents are likely to be similar to the thermal vents found in the deep ocean trenches here on Earth, where scientists have found unique forms of life energised not by the Sun but by geothermal energy (or volcanism). So all this adds up to the idea that a

similar thing may be happening on Jupiter’s frozen moon.

The water spouts recently observed by Hubble gives further evidence to the notion of a sub-ice liquid ocean on Europa. The water vapour plumes have been seen to rise to a height of 200 km above the surface, and it is estimated that about 7 tonnes of water per second is being ejected from the surface at about 700 metres per second. Despite the vigour of these emissions, the water has insufficient energy to escape Europa’s gravity field, and the water falls back onto the moon’s surface. Another characteristic is that the water erupts for around 7 hours at a time, and peaks when the moon is furthest from Jupiter, reinforcing the theory that the source of energy is derived from tidal effects in the moon.

This recent evidence is significant for three main reasons:

- it reinforces the theory that a subsurface ocean exists,

- it shows that the sub-ice ocean may be easily accessible from the surface,

- and thirdly, there may be organic molecules on Europa’s surface.

Clearly, since the findings of the Galileo spacecraft, there has been a lot of interest in sending robotic spacecraft to the surface of Europa to investigate the intriguing idea of life on Europa. It was believed that the ice crust may be kilometres thick, so that landing a sufficient source of energy to melt an access tunnel would be required to investigate the sub-ice ocean. Also, due to the moon’s relatively close proximity to Jupiter, it is very difficult to land a large payload mass on the surface of the moon, compounding this problem. However, the recent discovery of water vents suggests that the ocean may be more accessible than previously thought.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed