When the NASA probe Messenger arrived at Mercury in March 2011, and became the first Mercury orbiter, it too had to be designed to withstand a ‘hot environment’ – principally from the intense solar heating, but also the radiated heat from the hot planetary surface. However, the surface of Mercury is not uniformly hot. The planet has an orbit period (year) of 88 Earth days, and rotates on its axis (day) every 176 Earth days, so curiously Mercury has a length of day which is twice as long as its year. Consequently, the dark side of the planet has plenty of time to cool, and achieves minimum temperatures down to -200 degrees Celsius. Furthermore there are regions on the surface, near the poles, where the Sun never shines.

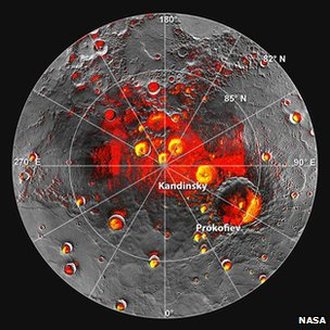

Recent, and surprising, findings from the Messenger spacecraft strongly indicate the presence of billions of tonnes of water at the north pole of the planet. The deposits lie deep within craters, where the intense Sun never rises. The ice is also buried under an insulating layer (tens of centimetres thick) of dark material, which is rich in organic molecules.

Project scientists believe that the huge quantities of ice and organics were deposited by impacting objects (such as comets) during the early history of the Solar System – which raises interesting questions about the consequences of similar impacts that the Earth would have encountered during the same historical epoch.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed